Webb, J, Ph.D.

When people undergo a great trauma or other unsettling event—they have lost a job or a loved one dies, for example—their understanding of themselves or of their place in the world often disintegrates, and they temporarily "fall apart," experiencing a type of depression referred to as existential depression.

It's very hard to keep your spirits up. You've got to

keep selling yourself a bill of goods, and some people are better at

lying to themselves than others. If you face reality too much, it kills

you. ~ Woody Allen

Background

Existential Issues and Giftedness

Existential Issues and Dabrowski’s Theory

Dabrowski

implied that gifted individuals are more likely to experience

existential depression; several concepts within his theory of positive

disintegration explain why gifted children and adults may be predisposed

to this type of depression (Mendaglio, 2008b). Fundamentally, Dabrowski

noted that persons with greater “developmental potential”—an inborn,

constitutional endowment that includes a high level of reactivity of the

central nervous system called overexcitability—have a greater awareness

of the expanse of life and of different ways that people can live their

lives, but this greater developmental potential also predisposes them

to emotional and interpersonal crises. Persons with heightened

overexcitabilities in one or more of the five areas that Dabrowski

listed—intellectual, emotional, imaginational, psychomotor, and

sensual—perceive reality in a different, more intense, multifaceted

manner. They are likely to be more sensitive than others to issues in

themselves and in the world around them and to react more intensely to

those issues. To the extent that they have intellectual

overexcitability, they are more likely to ponder and question. Their

emotional overexcitability makes them more sensitive to issues of

morality and fairness. Their imaginational overexcitability prompts them

to envision how things might be. Overall, their overexcitabilities help

them live multifaceted and nuanced lives, but these same

overexcitabilities are also likely to make them more sensitive to

existential issues.

Other Psychological Theorists

There are

several other psychological theorists whose writings provide concepts

that support and/or extend Dabrowski’s concepts, particularly as they

relate to existential issues and depression. The psychologist George

Kelley (1955) noted that humans do not enter a world that is inherently

structured; we must give the world a structure that we ourselves create.

Thus, we create psychological constructs, largely through language, to

make sense out of our experiences of the world.

A Journey into Existential Depression

Most of

us have grown up in families with predictable behaviors and traditions.

Family members are like planets in a solar system which have reached an

equilibrium regarding how they interact with each other. The rules of

interaction are reasonably clear, and family environment is predictable.

It is in such families that we acquire expectations of ourselves and

the world around us, and this is where we develop our values and beliefs

of how things “should be.”

Learning to Manage Existential Issues and Depression

How

does one learn to manage existential issues? First, people must

undertake to know themselves. Gifted adults commonly have the experience

of being “out of sync” with others but not understanding how or why

they are different. Jacobsen (2000) describes how people came to her in

her clinical practice with a vague sense that they were different;

others had told them repeatedly that they were “too-too”—that is, too

serious, too intense, too complex, too emotional, etc. However, as these

gifted adults came to understand that such behaviors were normal for

people like themselves, their anxiety about it lessened.

Coping Styles and Strategies

A Personal Coat of Arms

Roles and Role Stripping

Interpersonal Relationships

Self-Management

Life Meaning

Conclusion

Dreams

Hold fast to dreams,

for if dreams die,

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.

Hold fast to dreams.

For if dreams go,

Life is a barren field

Covered with snow.

About the Author

When people undergo a great trauma or other unsettling event—they have lost a job or a loved one dies, for example—their understanding of themselves or of their place in the world often disintegrates, and they temporarily "fall apart," experiencing a type of depression referred to as existential depression.

When people undergo a great trauma or other unsettling

event—they have lost a job or a loved one dies, for example—their

understanding of themselves or of their place in the world often

disintegrates, and they temporarily "fall apart," experiencing a type of

depression referred to as existential depression. Their ordeal

highlights for them the transient nature of life and the lack of control

that we have over so many events, and it raises questions about the

meaning of our lives and our behaviors. For other people, the experience

of existential depression seemingly arises spontaneously; it stems from

their own perception of life, their thoughts about the world and their

place in it, as well as the meaning of their life. While not universal,

the experience of existential depression can challenge an individual’s

very survival and represents both a great challenge and at the same time

an opportunity—an opportunity to seize control over one's life and turn

the experience into a positive life lesson—an experience leading to

personality growth.

It has been my experience that gifted and talented

persons are more likely than those who are less gifted to experience

spontaneous existential depression as an outgrowth of their mental and

emotional abilities and interactions with others. People who are bright

are usually more intense, sensitive, and idealistic, and they can see

the inconsistencies and absurdities in the values and behaviors of

others (Webb, Gore, Amend, & DeVries, 2007). This kind of sensitive

awareness and idealism makes them more likely to ask themselves

difficult questions about the nature and purpose of their lives and the

lives of those around them. They become keenly aware of their smallness

in the larger picture of existence, and they feel helpless to fix the

many problems that trouble them. As a result, they become depressed.

This spontaneous existential depression is also, I

believe, typically associated with the disintegration experiences

referred to by Dabrowski (Daniels & Piechowski, 2009; Mendaglio,

2008a). In Dabrowski's approach, individuals who “fall apart” must find

some way to “put themselves back together again,” either by

reintegrating at their previous state or demonstrating growth by

reintegrating at a new and higher level of functioning. Sadly, sometimes

the outcome of this process may lead to chronic breakdown and

disintegration. Whether existential depression and its resulting

disintegration become positive or whether they stay negative depends on

many factors.

I will focus my discussion here on characteristics of

people, especially the gifted, that may lead them to spontaneous

existential depression, relate these to Dabrowski’s theory of positive

disintegration, as well as to other psychological theories, and then

discuss some specific ways to manage existential depression.

A Polish psychiatrist and psychologist, Kazimierz

Dabrowski worked and wrote prolifically about his ideas in the years

from 1929 until his death in 1980, living part of his life in the United

States and in Canada, as well as in Europe. Nonetheless, he remains

largely unknown in North America, despite his many publications and even

though he was friends with prominent psychologists such as Maslow and

Mowrer. Although his theory of positive disintegration is highly

relevant to understanding existential depression—as well as many other

issues—I myself did not become aware of Dabrowski’s work until about 10

years ago.

But long before I knew about Dabrowski’s theory, I knew

about and understood existential depression. In fact, I knew it on a

personal level, for I have lived it. Like so many leaders in various

fields, particularly those men and women who have a deep passion for a

particular “cause”—whether connected to religion, government,

healthcare, the environment, or education—I experienced it because I saw

how the world was not the way I thought it should be or could be. There

were several periods in my life during which I was so “down” that it

was truly an effort to see any happiness around me. The result is that

now, whenever I think about existential depression, it rekindles within

me, bringing into conscious awareness thoughts and feelings that, most

of the time, I would rather ignore or avoid—thoughts of hopelessness and

despair for our world.

I have come to realize that once one becomes aware of

and involved in thinking about the many existential issues, one cannot

then go back to one's former life. As the saying goes, “Once you ring a

bell, you cannot unring it.” Like so many others, I continue to strive

to manage how these issues impact me, as well as the depression that

often accompanies them. In truth, this low-grade and chronic depression

is not necessarily a bad thing. After all, it reflects my underlying

dissatisfaction with the way things are, with the way I am, and with the

way the world is, and it leads me to continue striving to do better in

order to give my life meaning and to help others find meaning. But I

admit that sometimes I do envy people who have never experienced this

kind of depression.

Dabrowski’s ideas have given me a helpful cognitive

framework for understanding existential depression, as I am sure they

have similarly helped others. And although my relatively recent

discovery of Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration is new when

compared with my understanding of other theories in psychology, those

other theories are also useful and provide a foundation for

comprehending existential depression. After all, existential issues are

not new; existential thought appears in writings of many past centuries.

I first became aware of existential issues as a college

freshman when I was assigned to room with a student who was older than

I—in his mid thirties. Having been in the Navy, he was far more

experienced with many different kinds of people and many different ways

in which people choose to live their lives. He was a thoughtful

agnostic. I, on the other hand, had grown up in the Deep South in an

insular culture that had limited vision and rigid beliefs; my loving

parents were traditionally religious and tried to live conforming,

righteous, and conventional lives. My father, a dentist, made a good

living, and we attended church on Sundays. Until my college experience, I

thought that my family’s life was the way things were supposed to be; I

thought that everyone should share those same values, behaviors, and

world views.

My roommate, to whom I owe much gratitude, patiently

listened as I tried to persuade him of the validity and righteousness of

my limited views, after which he gently asked questions that required

me to think in ways I had not considered before. He quietly pointed out

the arbitrariness and meaninglessness of the many ways in which people,

including me, lived their lives, as well as the inconsistencies and

narcissistic grandiosity in many people’s beliefs. He introduced me to

Voltaire’s Candide and to philosophers like Sartre, Nietzsche,

and Kierkegaard. It was all quite a shock to me, because up to that

point, I had thought I had the world pretty well figured out.

In my coursework I was also exposed to some of the

well-known existential theologians—Paul Tillich (Protestant), Jacques

Maritain (Catholic), Martin Buber (Jewish), James Pike (Protestant), and

Alan Watts (Zen Buddhist)—all of whom were trying make sense of life

from a religious viewpoint. As I studied and learned, I began to see for

myself the hypocrisies and absurdities in the lives of so many people

around me, including my parents and myself, and I became quite

depressed. Fortunately, a kind and caring psychology professor allowed

me to meet with him for several sessions to talk about my angst and

disillusionment, or I might have imploded. Thanks to this professor, who

in many ways saved my life, I slowly began the process of learning to

manage my discontent and depression so that it could work for me rather than against

me. I changed my major to psychology, and in graduate school, I learned

that many others before me—certainly those who were introspective and

thoughtful idealists—had grappled with similar existential issues and

existential depression throughout the centuries.

While I was in graduate school, the humanistic psychologist Rollo May edited a book titled Existence: A new dimension in psychiatry and psychology

(1967). This book highlighted an entire area within psychology that

centered on existential issues. May became one of the most widely known

spokespersons on existential psychology, and the book continues to be a

classic. It was built on the writings of philosopher Martin Heidegger,

who emphasized phenomenology—the phenomena of being aware of one’s own

consciousness of the moment. Heidegger had written about Dasein, or “being there” in the moment with oneself and with how one perceives the world.

Other writers in May’s landmark book focused on the

applications of existential awareness to psychoanalysis and

psychotherapy, raising fundamental questions for therapists such as,

“How do I know that I am seeing the patient as he really is, in his own

reality, rather than merely a projection of our theories about him?” or

“How can we know whether we are seeing the patient in his real

world...which is for him unique, concrete, and different from our

general theories of culture?” (May, 1967, pp. 3-4). Or, said another

way, “…what is abstractly true, and what is existentially real for the

given living person?” (p. 13). As therapists, we have never participated

directly in the world of our patients, and yet we must find a way to

exist in it with them if we are to have any chance of truly knowing

them. We have experienced the world in our own way, with our own family

and our own culture. In our attempts to understand others, we generalize

from our own experiences and expect others to think, react, and be like

us. How can we see the world as our clients see it?

Although many early existential psychologists and

psychiatrists were neo-Freudians, they differed notably in focus from

Freud. Instead of concentrating on a patient’s past, pioneers such as

Otto Rank also focused on the “present time.” Karen Horney emphasized

“cultural approaches” and “basic anxiety from feeling isolated and

helpless.” And Harry Stack Sullivan highlighted the importance of one’s

experiences in interpersonal relationships in the “here and now,” as

well as what one has learned from one’s family environment. These

neo-Freudians believed that only by considering the present and a

person’s current experience could we understand that person. In

actuality, they were building off of even earlier concepts from

philosophers and theologians who had struggled with the meaning of

existence, as well as with how one’s perceptions color one’s

life—philosophers from as far back as Socrates in his dialogues and

Saint Augustine in his analyses of the self.

It is well-known that many famous artists and musicians

have experienced existential depression (Goertzel, Goertzel, Goertzel,

& Hanson, 2004; Piirto, 2004). Eminent persons who have suffered

from this kind of depression include Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner,

Charles Dickens, Joseph Conrad, Samuel Clemens, Henry James, Herman

Melville, Tennessee Williams, Virginia Woolf, Isak Dinesen, Sylvia

Plath, Emily Dickinson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Eleanor Roosevelt,

Abraham Lincoln, and Dag Hammarskjöld. In fact, the famous 17th century

gifted mathematician, physicist, and philosopher Blaise Pascal

(1623-1662) fully captured the experience of existential awareness when

he said, “When I consider the brief span of my life, swallowed up in the

eternity before and behind it, the small space that I fill, or even

see, engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces which I know not, and

which know not me, I am afraid, and wonder to see myself here rather

than there; for there is no reason why I should be here rather than

there, nor rather now than then” (Pascal, 1946).

Yalom (1980), who is perhaps the most widely read

current Western writer on existential psychotherapy, describes four

primary issues of existence (or "ultimate concerns")—death, freedom,

isolation, and meaninglessness. Death is an inevitable occurrence.

Freedom, in an existential sense, refers to the absence of external

structure—that is, humans do not enter a world that is inherently

structured. We must give the world a structure, which we ourselves

create. Thus, we have social customs and traditions, education,

religion, governments, laws, etc. Isolation recognizes that no matter

how close we become to another person, we will never completely know

that person and no one can fundamentally come to know us; a gap always

remains, and we are therefore still alone. The fourth primary issue,

meaninglessness, stems from the first three. If we must die, if in our

freedom we have to arbitrarily construct our own world, and if each of

us is ultimately alone, then what absolute meaning does life have?

People are most often affected by existential issues as

a result of their own experience of puzzlement from trying to

understand themselves and the world, which then generates feelings of

aloneness and existential depression. The people who worry over these

issues are seldom those in the lower reaches of intelligence or even in

the average range. In my experience, existential fretting, or for that

matter rumination and existential depression are far more common among

(though not exclusive to) more highly intelligent people—those who

ponder, question, analyze, and reflect. This is not surprising since one

must engage in substantial thought and reflection to even consider such

notions. People who mindlessly engage in superficial day-to-day aspects

of life—work, meals, home duties, and chores—do not tend to spend time

thinking about these types of issues. Brighter individuals are usually

more driven to search for universal rules or answers, and also to

recognize injustices, inconsistencies, and hypocrisies.

Other characteristics of gifted children and adults

also predispose them to existential distress. Because brighter people

are able to envision the possibilities of how things might be, they tend

to be idealists. However, they are simultaneously able to see that the

world falls short of their ideals. Unfortunately, these visionaries also

recognize that their ability to make changes in the world is very

limited. Because they are intense, these gifted individuals—both

children and adults—keenly feel the disappointment and frustration that

occurs when their ideals are not reached. They notice duplicity,

pretense, arbitrariness, insincerities, and absurdities in society and

in the behaviors of those around them. They may question or challenge

traditions, particularly those that seem meaningless or unfair. They may

ask, for example, “Why are there such inflexible sex or age-role

restrictions on people? Is there any justifiable reason why men and

women ‘should’ act a certain way? Why do people engage in hypocritical

behaviors in which they say one thing but then do the opposite? People

say they are concerned with the environment, but their behaviors show

otherwise. Why do people say things they really do not mean at all? They

greet you with, ‘How are you?’ when they really don’t want you to tell

them the details of how you are. Why are so many people so unthinking

and uncaring in their dealings with others? And with our planet? Are

others really concerned with improving the world, or is it simply all

about selfishness? Why do people settle for mediocrity? People seem

fundamentally selfish and tribal. How much difference can one person

make? It all seems hopeless. The world is too far gone. Things get worse

each day. As one person, I’ll never be able to make a difference.”

These thoughts are common in gifted children and adults.

As early as first grade, some gifted children,

particularly the more highly gifted ones, struggle with these types of

existential issues and begin to feel estranged from their peers. When

they try to share their existential thoughts and concerns with others,

they are usually met with reactions ranging from puzzlement to

hostility. The very fact of children raising such questions is a

challenge to tradition and prompts others to withdraw from or reject

them. The children soon discover that most other people do not share

their concerns but instead are focused on more concrete issues and on

fitting in with others' expectations. The result for these gifted

youngsters is conflict, either within themselves or with those around

them. But as George Bernard Shaw once said, “The reasonable man adapts

himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt

the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable

man.”

As they get older, gifted children may find that even

their families are not prepared to discuss and consider such weighty

concerns. They “may have to search far and wide to find others who share

their sometimes esoteric interests or even to find someone who laughs

at their sometimes quirky jokes. This challenge follows young gifted

adults into the workplace, where the entry-level positions that they

find themselves in can result in their being lost in the crowd, unable

to find others with whom they otherwise might feel a genuine sense of

connectedness” (Fiedler, 2008, p. 170).

Although they want to relate to others, gifted

individuals often encounter what Arthur Jensen (2004) has described as

an intellectual “zone of tolerance”—that is, in order to have a

long-lasting and meaningful relationship with another person, that

person should be within about plus or minus 20 IQ points of one’s

ability level. Outside of that zone, there will be differences in

thinking speed and depth or span of interests, which will likely lead to

impatience, dissatisfaction, frustration, and tension on the part of

each participant.

Gifted children and adults are often surprised to

realize that they are different. It is painful when others criticize

them for being too idealistic, too serious, too sensitive, too intense,

too impatient, or as having too weird a sense of humor. Gifted children,

particularly as they enter adolescence, may feel very alone in an

absurd, arbitrary, and meaningless world, which they feel powerless to

change. They may feel that adults in charge are not worthy of the

authority they hold. As one child described it, they feel “like

abandoned aliens waiting for the mother ship to come and take them home”

(Webb, Amend, Webb, Goerss, Beljan, & Olenchak, 2005, p. 136). This

alienation creates social and emotional issues for them with their age

peers, as well as with their teachers, which only adds to the

possibility of depression.

When their intensity is combined with

multi-potentiality—giftedness in several areas—these youngsters may also

become frustrated with the existential limitations of space and time.

Although they try to cram 27 hours worth of living into a 24-hour day,

there simply isn’t enough time to develop all of the talents and

interests that they may have. They have to make choices, but the choices

among so many possibilities feel unfair because they seem arbitrary;

there is no "ultimately right" choice. Choosing a college major or a

vocation is difficult when one is trying to make a decision between

passion and talent in areas as diverse as violin, genetics, theoretical

mathematics, and international relations. How can one be all that one

can be? In truth, one cannot be all that one “could” be in every area.

This realization can be very frustrating.

The reaction of gifted youngsters (again with

intensity) to these frustrations is often one of a righteous

indignation—they feel, “It isn’t right!” or “It isn’t fair!” But they

quickly discover that their anger is futile; they realize that it is

ineffective when directed at "fate" or at other circumstances which they

are not able to control. Anger that is powerless evolves quickly into

depression. It is a type of “learned helplessness,” a phrase coined by

psychologist Martin Seligman (1991). “I’m helpless; I can’t solve this.”

In such depression, people typically—and often

desperately—try to discover some sense of meaning, some anchor point

that they can grasp that will allow them to pull themselves out of the

mire and muck of injustice or unfairness. Often, though, the more they

try to struggle out of—or wallow in—their depression, the more they

become acutely aware that their life is brief and ultimately finite,

that they are alone and are only one very small organism in a very large

world, and that there is a frightening freedom and responsibility

regarding how one chooses to live one's life. They feel disillusioned,

and they question life's meaning, often asking themselves, "Is this all

there is to life? Isn’t there some ultimate and universal meaning? Does

life only have meaning if I give it meaning? I am one small,

insignificant organism alone in an absurd, arbitrary, and capricious

world where my life can have little impact, and then I just die. Is this

all there is?" Questions like this promote a sense of personal

disintegration.

Such concerns are not surprising in thoughtful adults

who are going through some sort of quarter-life or mid-life crisis.

However, it is startling and alarming when these sorts of existential

questions are foremost in the mind of a 10- or 12- or 15-year-old. Such

existential depressions in children deserve careful attention, since

they can be precursors to suicide.

Dabrowski also emphasized the role of socialization,

which he called the “second factor,” as a key force influencing personal

development, though the amount of a culture’s influence varies with

each person’s inborn developmental potential. Nevertheless, the social

environment often squelches autonomy, and “adjustment to a society that

is itself ‘primitive and confused’ is adevelopmental [i.e., hinders

development] and holds one back from discovering individual essence and

from exercising choice in shaping and developing one’s self…” (Tillier,

2008, p. 108). Even so, when one becomes more aware of the scope and

complexity of life and of one’s culture, one begins to experience

self-doubt, anxiety, and depression; Dabrowski emphasized that all of

these—as discomforting as they are—are necessary steps on the path

toward heightened development. Thus, as one becomes more aware of “what

ought to be” rather than just “what is,” he or she experiences

increasing discomfort and disillusionment, often leading to a personal

disintegration that, according to Dabrowski, is a necessary step before

one can reintegrate at a higher level of acceptance and understanding—a

new level representing growth.

Reintegration at a higher level is not a certainty,

though. Whether or not one is in fact able to reintegrate depends on

what Dabrowski called the “third factor”—an inner force, largely inborn,

that impels people to become more self-determined and to control their

behaviors by their inner belief/value matrix, rather than by societal

conventions or even their own biological needs. This third factor allows

people to live their lives consciously and deliberately, acting in

accordance with their own personal values. The dynamic of the third

factor drives people toward introspection, self-education, and

self-development, and it allows them to reintegrate themselves at a

higher level so that they can transcend their surroundings in a highly

moral and altruistic fashion. Some individuals, however, may

disintegrate and fail to reintegrate at a higher level, or they may stay

at the same level as before. Of course it is desirable to reintegrate

at the higher level.

Dabrowski’s descriptions of integration and

disintegration are important but are also complex, so I will provide

only the highlights of those that are particularly relevant to

existential depression. In Dabrowski’s view, there are two types of

integration—primary and secondary—and four types of

disintegration—positive, negative, partial, and global.

- Primary integration characterizes individuals who

are largely under the influence of the first factor (biology) and the

second factor (environment). These individuals experience the human life

cycle and may become very successful in societal terms, but they are

not fully developed human beings. Persons characterized by secondary

integration are influenced primarily by the third factor; they are inner

directed and values driven. As fully human, they live life

autonomously, authentically, and altruistically. Biological drives are

sublimated into higher modes of expression. Conformity and nonconformity

to societal norms are principled. Movement from primary to secondary

integration arises from positive disintegration. (Mendaglio, 2008b, p.

36)

Positive disintegration involves a two-step process.

First, the lower primary integration—which involves little, if any,

reflection—must be dissolved; subsequently, one must reintegrate to

create a higher level of functioning (Dabrowski, 1970). During the first

step of dissolution, individuals experience “…intense external and

internal conflicts that generate intense negative emotions. Such

experiencing may be initially triggered by developmental milestones,

such as puberty, or crises, such as a painful divorce or a difficult

career event or the death of a loved one. As a result, individuals

become increasingly conscious of self and the world. They become more

and more distressed as they perceive a discrepancy between the way the

world ought to be and the way it is…”(Mendaglio, 2008b, p. 27). The way

these persons view and structure the world is thrown into ambiguity and

turmoil, along with the internal guidelines that they have thoughtlessly

adopted from society to guide their daily behaviors. The external

structure that they are steeped with becomes contradictory or

meaningless when confronted with articulate, conscious individual

experience.

Because people can only stand conflict and ambiguity

for a relatively brief time, they will create a new mental organization

as they attempt to reduce their anxiety and discomfort. However, this

new mental schema may be only partially successful; these individuals

may find themselves aware of inconsistencies and pretenses within their

new way of thinking, though they may try desperately to convince

themselves otherwise. They experience, then, only the dissolving part of

the process—without reintegration at a higher level—leaving them with

negative disintegration and the accompanying conflicts and negative

emotions. Worse, they are unable to return to their previous unthinking

way of being (“the rung bell”). Some individuals, usually those with

substantial initial integration and limited potential to develop, will

fall back and reintegrate at their previous level; others find

themselves stuck in disintegration—a serious situation that Dabrowski

said could lead to psychosis or suicide.

According to Dabrowski, some people are in fact able to

complete both parts of the process—both disintegration and subsequent

positive reintegration. They develop an acceptance of their

self-awareness and self-direction in ways that allow them to select

values that transcend the immediate culture and are from then on focused

on more universal, humanistic, and altruistic values. They may select a

new vocation in which they can use their altruistic vision or a new

partner with whom they can share their important values. This

higher-level mental organization allows more of a sense of personal

contentment with a striving to continually improve, though these people

will likely still experience episodes of disintegration, discomfort, and

reintegration as their awareness continues to grow.

- Man looks at his world through transparent templets

which he creates and then attempts to fit over the realities of which

the world is composed. (pp. 8-9)

Constructs are used for predictions of things to come, and the world keeps on rolling on and revealing these predictions to be either correct or misleading. This fact provides the basis for the revision of constructs and, eventually, of whole construct systems. (p. 14)

The Gestalt theorists, such as Fritz Perls, Ralph

Hefferline, and Paul Goodman, emphasized two central ideas: (1) we all

exist in an experiential present moment, which is embedded in webs of

relationships; (2) thus, we can only know ourselves against the

background of how we relate to other things—i.e., a figure-ground

relationship (Perls, Hefferline, & Goodman, 1972). They also pointed

out that humans have an inborn tendency to seek closure and, as a

result, have little tolerance for ambiguity. Similarly, the little-known

theorist Prescott Lecky (1969) hypothesized that humans are born with

an instinctual drive to seek consistency as a way of making sense of the

world around them, a notion that is similar to Leon Festinger’s (1957)

observation that humans will strive arduously to reduce the

uncomfortable psychological tension created by “cognitive dissonance”

that arises if we have an inconsistency among our beliefs or behaviors.

The neo-Freudian Alfred Adler stated that people, in

their attempt to gain mastery over their world, create “fictional

finalisms”—invented concepts that cannot be proven, yet people organize

their lives around them as though they are true (Hoffman, 1994). Since

ultimate truth is beyond the capability of humans, we create partial

truths about things that we cannot see, prove, nor disprove. Examples

range from the lighthearted (e.g., Santa Claus) to serious sweeping

philosophical statements (e.g., “We can control our own destiny” or

“There is a heaven for the virtuous and a hell for sinners”). These

fictional finalisms ameliorate our anxiety and help us feel more in

control of our world. We prefer the comfort of dogmatic certainty to the

chaos of questioning or of the insecurity and uncertainness of the

unknown. As Freud noted, “All fantasies to fulfill illusions stem from

anxieties” (1989, p. 16); these are attempts to feel in control of

ourselves and the world around us.

The existentialist theologian Paul Tillich (1957) made a

similar observation about humans, which prompted him to redefine God

and religion. According to Tillich, God was whatever a person was most

ultimately concerned with, and religion was composed of whatever

behaviors that person engaged in to achieve that ultimate concern. In

other words, a person’s God could be money, or religion, or power, or

control, or fame—whatever a person created in order to try to organize

his or her life.

All of these theorists would comfortably agree that

people seek groups and partners who share their beliefs, which often

leads to false but reassuring certainty. These groups might embrace

religious or political causes, for example—all of which might be

altruistic and benevolent, but yet all of which are likely to require a

certain amount of conformity and fitting in at the expense of our

individualism. Conformity can be comforting; being an individual,

particularly if one is challenging traditions, is often uncomfortable.

Dabrowski clearly believed that one cannot evolve into a fully developed

and authentic person without developing an individualistic, unique, and

conscious inner core of beliefs and values. He also understood that

this road was arduous and fraught with discomfort and pain. One must

first disintegrate before one can reintegrate at a higher level, and

that the process of subsequent incremental disintegrations and

reintegrations is likely to continue throughout one’s entire life.

However, our families are not always places of perfect

acceptance and happiness; children do things that displease their

parents, and parents do not satisfy all of the desires of their children

(nor should they, necessarily). When children’s feelings are hurt, they

begin to withdraw into themselves and put up protective barriers. They

are not as open as they once were; they are more evaluative and more

cautious—all part of the process of becoming an individual, separate

from parents and family.

As children grow, they become exposed to people outside

of the family, and they discover that others do not share the same

expectations, values, or behaviors. Questions arise. “Why? Which set of

values and behaviors is better? Which is right? How shall I choose?”

They see that some behaviors by others are entirely contradictory to the

ways in which they themselves were raised.

The brighter that people are, the more likely they are

to be aware of how their own belief/value system is inconsistent with

that of others. They may also see inconsistencies within their own

belief/value system—their values are out of sync with the way they feel!

Tension and discomfort arises. They may experience an

approach-avoidance conflict about such awareness. On the one hand, they

want to become more aware of these inconsistencies and absurdities in

order to be fair and consistent and to learn better ways of being, yet

on the other hand, they want to avoid such awareness because it makes

them uncomfortable and challenges them to examine themselves—not always a

flattering activity—as they try to live a more thoughtful, consistent,

and meaningful life. These individuals adopt one or a combination of

basic coping styles first described by the neo-Freudian Karen Horney

(1945): (1) moving toward—accepting society’s traditions; conforming;

working the system to become successful, (2) moving away from—rejecting

traditional society via withdrawal; being nontraditional and arcane, and

(3) moving against—rebelliously rejecting society; being angry and

openly nonconforming.

As these people gain more life experience, their

perspectives shift. They recognize that Socrates was right when he said,

“The unexamined life is not worth living.” Yet examining life can be

discomforting. For many, certain life milestones are awakening

experiences—for example, birthdays (turning 21, 30, 40, etc.) and

anniversaries; school and college reunions; weddings and funerals;

estate planning and making a will. People find that they want to change

their way of living so that they are not simply playing out the roles

that others expect of them, but it is difficult to give up old

traditions and habits, as well as the connectedness that these customs

and practices offer.

People find that whenever they challenge or violate a

tradition, it makes others uncomfortable. We want people to be

predictable, even if it means that they are behaving in illogical and

nonsensical ways. Most people vacillate in their thinking and behaviors;

they can see how they might be and how they actually are, but making a

leap forward to change is difficult. They may also find themselves

feeling angry because they feel powerless to make the changes that they

see as needed.

As people grow older, the developmental challenges that

they encounter make them progressively more aware of existential issues

and increase the likelihood of existential depression. Erikson (1959),

Levinson (1986), and Sheehy (1995, 2006) have described a series of

adult life stages, each of which has developmental tasks associated with

it. A blended summary of the relevant adult stages is as follows:

Age 18-24 “Pulling up roots” – Breaking away from home Age 25-35 “Trying 20s” – Establishing oneself as an adult; making career choices; coming to grips with marriage, children, society Age 35-45

“Deadline decade” – Authenticity crisis; realization that it is the

halfway point in one’s life; re-evaluation of oneself and one’s

relationships; making choices about pushing harder vs. withdrawing vs.

changing one’s life Age 45-55 “Renewal or resignation” – Further

redefinition of priorities; changing or renewing relationships; roles

change; children leave home; parents age or die; physical changes in

self; further realization of own mortality Age 55+ “Regeneration”

– Acceptance/rebellion at prospect of retirement; friends/mentors die;

evaluation of life’s work; new relationship with family; physical

changes; self-acceptance or rejection

Although most people go through these stages during the

ages listed above, it is my experience that gifted adults usually

encounter these life stages earlier and more intensely than others. As

they grope with these issues, they are likely to experience related

problems involving marital rapport and communication, expectations and

relationships with their children, dissatisfaction with co-workers, and

discontent with themselves. In Dabrowski terms, they experience

disintegration, with existential depression as a main component.

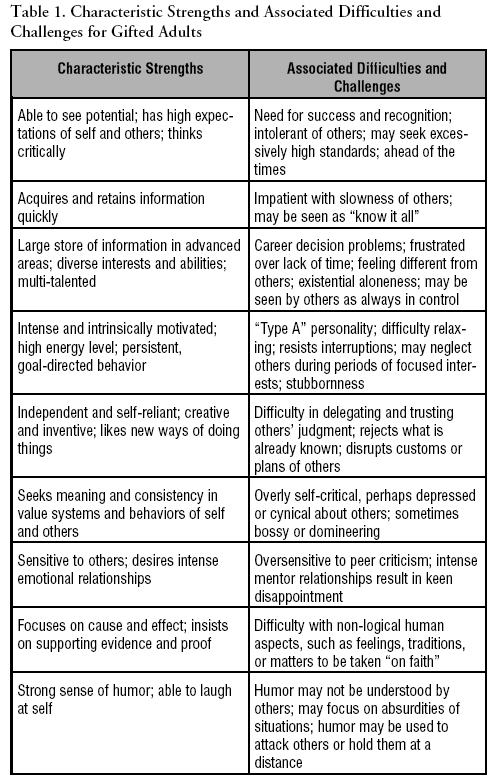

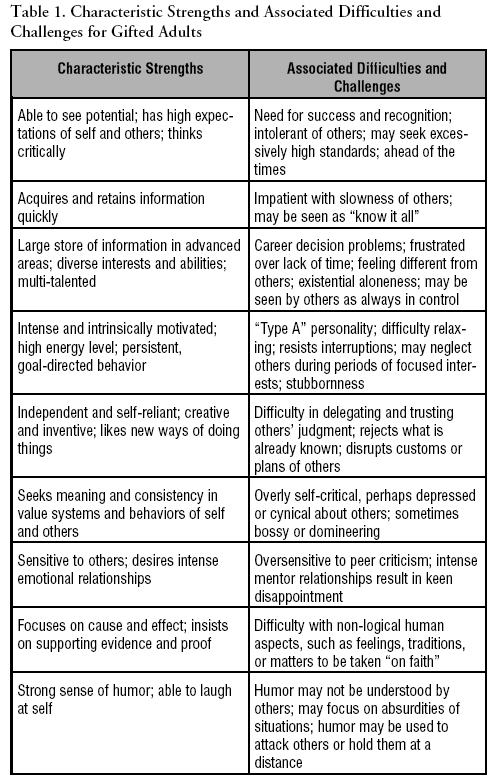

It is evident, then, that being bright does not

necessarily mean that one will be content, happy, and successful—and

certainly not during periods of disintegration. More than 30 years ago,

psychologist May Seagoe (1974) composed a table in which she listed

characteristic strengths of gifted children on one side, and then on the

adjacent side, she listed possible challenges or problems that are

likely to arise from those very strengths. Table 1 is a similar table

for gifted adults.

These strengths and associated difficulties lead most

gifted adults to experience at least some existential conflicts that

they struggle with throughout their life (Jacobsen, 2000; Streznewski,

1999). Four of these conflicts occur with particular frequency and serve

as underpinnings for personal disintegration, creating significant

anxiety and depression for the individuals who struggle with them. They

are:

- Acceptance of others vs. disappointment and cynicism

- Acceptance of self vs. excessive self-criticism and depression

- Necessity of feelings vs. the efficiency of logic and rational approaches

- Finding personal meaning vs. tangible achievements

To reach positive reintegration, one needs to reach

some resolution, or at least a level of comfort, concerning ways to

manage (not to satisfy) the issues listed in the bulleted items above.

Along with knowing oneself, it is important to come to

grips with three truths pointed out long ago by the philosopher Arthur

Schopenhauer (2004). He emphasized the importance of knowing and

developing ourselves, stating that: (1) what we have as material goods

are temporary, transient, and not able to provide us with lasting

comfort; (2) what we represent in the eyes of others is as ephemeral as

material possessions, since the opinions of others may change at any

time; besides, we can never know what others really think of us anyway;

and (3) what we are is the only thing that truly matters. Polonius, in

Shakespeare’s Hamlet, says, “This above all: to thine own self be

true,/And it must follow, as the night the day,/Thou cans't not be false

to any man.” Certainly, knowing oneself, including our weak areas, is

important. Knowing our thought patterns is also important. As Yalom

(2008) noted, “Inner equanimity stems from knowing that it is not things that disturb us, but our interpretations of things” (p. 113). What is our self-talk as we look at the world and at situations in our world?

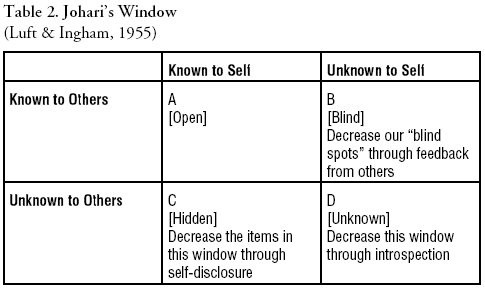

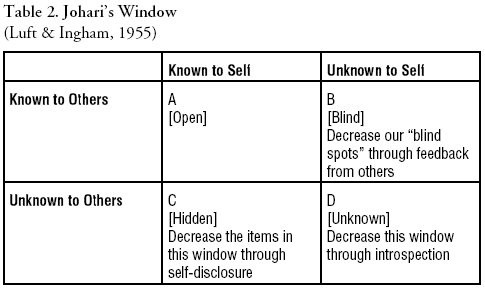

Next we should understand how we relate to others. Many

years ago, Luft and Ingham (1955), recognizing that all of us have

“blind spots” when it comes to how we see ourselves, developed a simple

matrix which they called Johari’s Window as a tool to help people

understand themselves, their blind spots, and their relationships with

others. To use Johari’s window, a person is given a list of 55

adjectives and instructed to select five or six that describe his or her

own personality. Peers of that person are then given the same list, and

they each choose five or six adjectives that describe the subject.

These adjectives are then put in the appropriate “window” below. The

person discovers which of the adjectives match what others have listed,

as well as which adjectives they listed that others did not. The results

can be extremely helpful in gaining self-understanding, including how

one is seen by others.

It is not enough, though, to simply know oneself. We

must also accept ourselves and find ways to nurture ourselves. Below are

some guiding principles I have found to be helpful and have shared with

others:

- Your life focus should be on principles and values rather than people.

- Developing yourself will likely require self-focus and probably some narcissism, but know that there is a difference between healthy narcissism and pathological narcissism.

- Your development will likely involve periods of disintegration and reintegration as you move toward increasingly positive disintegration.

- Your journey will probably make you and others around you uncomfortable.

When people experiencing disintegration know what they

might expect, as in the list above, the experience itself is not so

intimidating or frightening. There is hope that the individual will

reintegrate in a positive way, though the experience will be

uncomfortable for a time. In addition to this understanding, there are

several coping strategies that can be helpful, as well as other

behavioral styles that may appear helpful but really are not.

Coping with an ongoing awareness of existential issues

and the accompanying low-grade depression can be distressing, and few

people can directly confront their existential depression for very long.

As Yalom (2008) wrote, quoting François de La Rochefoucauld from the

1600s, “You cannot stare straight into the face of the sun, or death.”

How do people try to manage these complex and often painful issues? Some

coping styles are clearly less adaptive than others, especially when

they involve narrowing of thought and high activity levels. Some

frequent but not-so-effective styles are:

- Becoming narcissistic. Some individuals deal with painful issues in their life through narcissism. Their thought pattern is something like this: “I can protect myself (temporarily) from having to confront my own mortality by convincing myself of my own importance and that what I am doing is extremely important to the world.”

- Knowing the “truth.” Likewise, some individuals convince themselves that they are “right” and know the “truth.” Religions often facilitate such an attitude. Their thought pattern goes something like this: “If I can convince myself that I know the ‘truth’ about life and the universal meaning of existence, then I can gain comfort.” Often, this illusion is accompanied by an intolerance for others’ questions, beliefs, or style of living.

- Trying to control life, or at least label it. Another strategy is control. “Perhaps if I organize myself and my thinking in controlled, logic-tight compartments, then I can control life.” Labels help, because they give an illusion of control. If I have power over things around me, then I have power over my life and my destiny.

- Learning to not think. Still another pattern is to be non-thinking. “Sometimes it is simply less painful if I choose to just not think about things that matter, and certainly to avoid using critical thinking skills. I will selectively ignore areas of my life.” This allows blind spots to develop or exist.

- Learning to not care. I have known children and adults who have convinced themselves not to care; it is less painful that way. Unfortunately, many times this “numbing of the mind” is accomplished via alcohol, drugs, or other addictions.

- Keeping busy. Some individuals avoid facing difficult personal issues by keeping busy. Their inner voice tells them, “If I stay frantically busy in a hypomanic fashion, then I don’t have time to think about things, or about the meaning of my behaviors.” Sometimes these people are “trivial pursuers” in that they focus on possessing, creating, or developing minutiae or pleasant pastimes with little regard to whether their efforts are trivial or harmful. Others seem to have a compulsion to utter or to act to overcome their “horror vacui”—their fear of empty space or time, during which they might be forced to face their issues.

- Seeking novelty and adrenaline rushes. The psychologist Frank Farley (1991) has described a type “T” personality, in which the “T” stands for thrills through risk taking and seeking stimulation, excitement, and arousal. Some of these people may develop addictions—substance abuse, gambling, sexual addiction, and others. In some respects, type “T” behaviors are beneficial because, by pushing the limits of tradition, these individuals can promote creative behaviors. On the other hand, type “T” behaviors can easily become a substitute for authentic close relationships or for meaningful self-examination.

Other coping styles are more adaptive. They help

maintain a personal balance that increases the likelihood of

successfully managing disintegrations and existential issues. These

include:

- Coming to know oneself. An individual must "separate the wheat from the chaff" when it comes to his or her values and perception of the world. One’s unique characteristics and personality must be recognized, valued, and accepted. External mores and externally based perceptions and understandings of the world—the chaff—must be winnowed from one's own—however flawed and undeveloped—sense of the world.

- Becoming involved in causes. People who get involved with causes are almost always idealists. “When I am in a cause with others, whether the cause is academic, political, social, or even a cult, I feel less alone.” Sometimes, though, existential issues lead individuals to bury themselves so intensively in causes that they neglect to look at themselves.

- Maintaining a sense of humor. It has been said that if you push a tragedy far enough, it becomes a comedy. The everyday tragedies that we experience in our lives can be burdensome, but through comedy, we get a sense of relief and perspective. While life’s absurdities can be frustrating and distressing, finding humor in them (oftentimes by imagining them pushed to extremes) can prompt a more pragmatic—and sometimes realistic—view of things. Being able to laugh at a situation is a valuable asset; being able to laugh at oneself is even more important. Thus, a sense of humor can ameliorate our feelings of hopelessness about existential issues.

- Touching and feeling connected. One potent way of breaking through the sense of existential isolation is through touch. In the same way that infants need to be held and touched, so do persons who are experiencing existential aloneness. Touch is a fundamental and instinctual aspect of existence, as evidenced by mother-infant bonding or "failure to thrive" syndrome. Often, I have "prescribed" daily hugs for youngsters suffering existential depression and have advised parents of reluctant teenagers to simply say, "I know you may not want a hug, but I need a hug, so come here and give me a hug." A hug, a touch on the arm, playful jostling, or even a "high five" can be very important to such a youngster because it establishes at least some physical, tangible connection. Hugging and touching is very important in all cultures. Regrettably, our society seems increasingly wary about people touching each other.

- Compartmentalizing. It is not so much events that disturb us, but our interpretations of those events—our “self-talk.” Intense negative self-talk about a situation or one’s life can easily spread into “all or none” or “always” or “never” thinking that results in stress spilling over into all areas of a person’s life—for example, “I’m never going to feel happiness again!” or “I always feel alone. I’m never going to find anyone I can relate to, and that’s catastrophic!” The extent to which individuals are miserable depends heavily on their self-talk and whether they can learn to compartmentalize or section off the stress and, at least temporarily, quarantine that area. Some people have found it helpful to visualize putting the stress inside a box or “Worry Jar,” then shutting the lid and placing it on a shelf until they are ready to look at those worries again (Webb, Gore, Amend, & DeVries, 2007). They simply plan to deal with the issue at a later time, or they set aside a designated “worry time” just for that issue. Just because people are upset in one area of their life does not mean that they should be miserable about everything. Too much compartmentalization, however, can also result in problems. Sometimes people wall off their feelings so thoroughly that they have difficulty being “present” in the here and now, or they may intellectualize the problem into a compartment but never actually deal with the issue or the self-talk that created it in the first place. Some individuals develop such tight compartments that they cannot see how their behaviors and beliefs are actually contradictory—for example, environmental concerns juxtaposed against admiration for a gas-guzzling vehicle.

- Letting go. People who are intense often try to impose their will on the world around them in virtually all areas yet find themselves unsatisfied or unhappy with the outcome. Some years ago, there was a popular movie, My Dinner with Andre (1981), which featured two friends sharing their life experiences over an evening meal at a restaurant. In the film, Gregory, a theater director from New York and the more talkative of the two, relates to Shawn his stories of dropping out of school, traveling around the world, and experiencing the variety of ways in which people live, including a monk who could balance his entire weight on his fingertips. Shawn, who has lived his life frantically meeting deadlines and achieving, listens avidly but questions the value of Gregory's seeming abandonment of the pragmatic aspects of life. There is no resolution, but the film raises the question of how much one needs to try to control life versus whether it is better to just let go and flow with life.

- Living in the present moment. Living in the present (Dasein) is to be aware of what is happening to you, what you are doing, and what you are feeling and thinking. You look at situations as they are, without coloring them with previous experiences. You are not influenced by fears, anger, desires, or attachments. Living in such a way makes it easier to deal with whatever you are doing at the present moment. People in disintegrative states often focus heavily on the past or on the future, which looks so bleak to them, rather than living in the present.

- Learning optimism and resiliency. Optimism significantly affects how people respond to adversity and difficulty. Although there is a genetic predisposition toward optimism or pessimism, and even toward depression, depression is greatly influenced by how an individual has learned to react to what happens in his or her life. Though people can do little about their genetics, their reaction to situations, including their self-talk, will determine their optimism and resiliency.

- Focusing on the continuity of generations. For some, focusing on the continuity of generations—children and grandchildren—is comforting; for others, it is disturbing because they see the world as being so full of difficulties that they worry over what their children will face. Nevertheless, age does bring perspective such that one no longer “sweats the small stuff.” And most people, as they get older, find that they have wisdom that they can share with younger people, which helps them feel connected with at least some of humanity. Some have even written an ethical will to pass their values, ideals, and life philosophy on to their children and grandchildren (Webb, Gore, DeVries, & McDaniel, 2004). Most people, as they enter their later life, find ways to resolve existential issues, including the thought of dying, and come to reach some sense of peace and contentment.

- Being aware of “rippling.” Recently, I sat with a friend who was dying of lung cancer, and we talked about rippling—how the influence of his life had rippled out widely to affect the lives of people, many of whom he did not even know. I recalled Yalom’s (2008) statement that, “Of all the ideas that have emerged from my years of practice to counter a person’s death anxiety and distress at the transience of life, I have found the idea of rippling singularly powerful” (p. 83). “Each of us creates—often without our conscious intent or knowledge—concentric circles of influence that may affect others for years, even for generations” (p. 83).

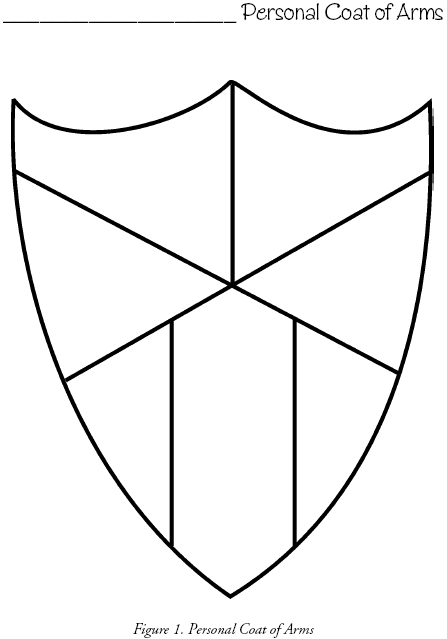

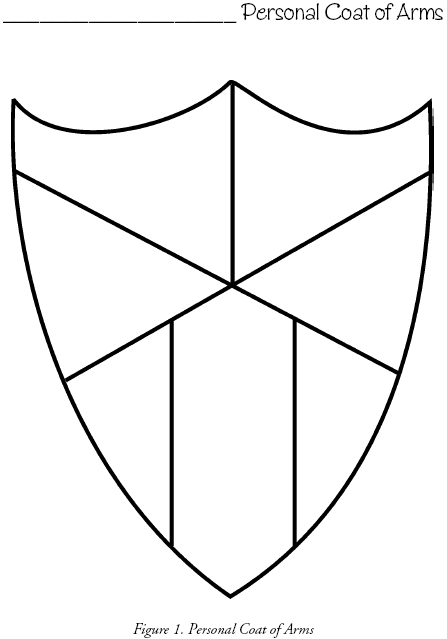

In the Middle Ages, families often had a coat of arms,

depicted by a shield containing symbols to represent and highlight

different aspects of that family’s tradition and heritage. A picture of a

sheaf of grain might symbolize that the family owned land; a sword

could depict family members who fought valiantly. Below is an exercise

to help individuals depict what is important to them—what they would

want their coat of arms to look like if we used such things today.

“Your Personal Coat of Arms” is an exercise shared with

me many years ago by a colleague that helps people think about the key

values they use to guide their life and the decisions they make. This

exercise can also help them decide which areas are core values for them

and which are simply a veneer of convenience or tradition.

Figure 1 shows an escutcheon that is subdivided. Here are the instructions for filling out your Personal Coat of Arms:

- First, title your shield by putting your name on the top.

- In each section of your shield, put the following:

- Choose one word that describes you, and draw a picture that represents that word in one panel of the shield.

- Draw a symbol to represent the social or political cause that you have done the most for in your lifetime.

- List two things that you have been struggling to become better at, and write them in one panel of the shield.

- Draw a picture or note a major fantasy of what you yearn to do or would do if you had no restrictions.

- Select three words that you would like people to use to describe you, and write or symbolize them in one panel of the shield.

- Draw something to represent what caused the greatest change in your way of living.

- Draw or symbolize the most important person in your life.

Now consider how central this coat of arms is in

your daily life. Do you use your coat of arms only to protect you, or

does it also represent something that you aspire to?

You probably noticed that much of what you wrote on

your Personal Coat of Arms had to do with your roles in life—perhaps as

parent, student, musician, friend, spouse, helper, entrepreneur,

adventurer—and roles certainly provide structure to our lives. But this

raises some important questions. How much of your identify and

self-worth come from the roles that you play? Do you define your roles,

or do they define you? Are the roles simply irrelevant traditions and

confining rituals, or do they give your life meaningful substance? Are

these roles how you want to live your life?

A solid sense of self cannot be built on roles. To do

so increases the likelihood of disintegration, because at some point,

all of our roles will be stripped from us. There will come a day when we

will no longer be a teacher or a business owner or musician or a

husband or a wife. We will no longer be someone’s child; our parents

will die, leaving us as orphans. I can substitute new roles for the ones

I have lost, but those may become lost, too. As I lose the roles that

organize my existence, I will find myself having to confront provocative

questions. What would I be like without my roles? What value would I

have? As I substitute new roles, are they truly ones that I want to

select?

Some years ago, a colleague in psychology introduced me

to a role-stripping exercise as a way of focusing thought on these

issues. It goes as follows:

- Identify the five most central roles in your life (mother, son, teacher, civic leader, etc.), and write them on a piece of paper.

- Rank these roles, with “1” being the most central to your life’s activities.

- Take role “5” and consider how it structures and fits into your life. Now throw it away. You no longer have it in your life.

- Take role “4” and contemplate how it structures and fits into your life. Now throw it away. You no longer have it in your life either.

- Continue discarding roles, one at a time with due consideration, until only one role is left. This is your central role, the one around which most of your life is focused.

- Now discard that role. What of you is left? Who are you without your roles? What value do you have?

After the role-stripping exercise, consider once again

how much your roles define you versus how much you define your roles.

You may wish to contemplate what others would be like without their

roles. What value would they have? Perhaps you might ask family members

and co-workers how they perceive your major roles. Their ideas might be

different! You may then decide to temporarily take “time out” from each

of your roles so that you can enrich or enhance other roles. Or you may

resolve to develop a new role or invent a new tradition for yourself or

your family.

Over the course of our lives, each of us develops a

persona—a façade that we put up for the world to protect ourselves from

others until we know that we can trust them well enough to lower that

façade. Behind this façade is where we cope with our own internal

existential issues, but it is also our façade that keeps others at a

distance and fosters our existential aloneness because it hinders them

from truly knowing us. This façade usually represents our lifestyle, and

behind the mask are our values; however, both lifestyle and values are

matters that we can choose to adopt or to discard. There are three

underlying existential facts. They are: (1) we are basically alone, (2)

we will die, and (3) we need others. Interpersonal relationships are

basic to human existence, yet we spend so much of our lives in

superficialities that we often give too little focus to meaningful

relationships. Here are some questions to consider:

- Do you have at least one person with whom you can be accepted without your roles?

- Are your relationships with others primarily authentic, or are they mostly roles?

- Do you need to be in control of others as much as you are, or can you release some of that control?

- Does your logic and analytical ability interfere with your ability to give and receive affection?

Existential isolation is eased to a degree if people

simply feel that someone else understands the issues that they are

grappling with. For example, even though your experience is not exactly

the same as mine, I feel far less alone if I know that your experiences

have been somewhat similar.

Many people have written about how important it is that

a person not be allowed to die alone, and hospice centers across the

country make sure that someone is present at the moment of death.

Anxiety about death is not a disease; it is simply a byproduct of life.

It seems that death—the final moment in our life as we know it—is a

topic that people avoid except in the abstract. However, we need to

think and talk about death if we are to live our lives well.

In our aloneness, particularly as we contemplate no

longer being in this world and no longer existing, we do need others. We

never outgrow our need for connectedness. Establishing relationships

with others typically goes through a sequence of three successive steps:

(1) inclusion/exclusion—“Am I a member of this group, or am I on the

outside?” (2) control—“Where do I fit in determining what we are going

to do? Am I the leader, the follower, the worker, etc.?” and (3) mutual

caring—“Do others really care about my concerns, and do I care about

theirs?” (Schutz, 1958). However, these three steps can actually

interfere with close relationships with others.

Here are some exercises you may find helpful for improving your relationships with others:

- Set aside five to 15 minutes of special time each day to let someone else be in control.

- As an exercise, convey and receive affection nonverbally.

- Touch other people more often, and regularly.

- Identify the “imperfections” in each of your relationships. How would your relationships change if you stopped trying to change these imperfections?

- Increase your self-disclosure, because self-disclosure promotes reciprocal self-disclosure in others.

- Offer others empathy, even when you are frightened or angry.

- Express gratitude to someone to whom you have never before expressed it.

These exercises should open the door to improved

relationships with others. They help people connect in new ways and

become more aware of their behaviors in relationships, including some

that may be hampering the relationship.

I have already noted the importance of accepting

oneself as valuable apart from one’s roles and separate from others’

evaluations. But learning to do this requires that people learn to

manage themselves. This involves them becoming more aware of

themselves—their roles, their coat of arms, their relationships—and then

learning to manage their self-talk about all of this. If they allow

themselves to explore as they do this, they may be able to discover

parts of themselves that do not fit with their roles.

Here are some things to try that will facilitate

your learning more about yourself, as well as learning new

self-management skills:

- Meditate for five to 15 minutes per day.

- Become aware of your self-talk. Then, measure the amount of your negative self-talk as compared with the amount of your positive self-talk.

- Minimize your self-control in selected situations.

- Be aware of “HALT” and its relationship to depression and cynicism. HALT stands for Hungry, Angry, Lonely, and Tired—all of which are conditions that predispose people to feeling overwhelmed. Nietsche said, “When we are tired, we are attacked by ideas we conquered long ago.”

Part of the human condition seems to be to search for

meaning. Throughout history, countless great works of literature have

focused on this theme. Victor Frankl, in his 1946 book Man’s Search for

Meaning, showed us that even in dire circumstances, such as a

concentration camp like Auschwitz, there is a great human need to find

meaning. Frankl himself, imprisoned and in desperate circumstances in

Auschwitz, searched for and found meaning in his relationships with

others and with loved ones, even though they were separated.

Unfortunately, the people who need meaning the most are

usually so busy achieving that they have little or no time to search

for it. Without meaning as an anchor, people are particularly at risk

for disintegration and existential depression. Frantic efforts at

achievement and control end up collapsing because they are hollow

underneath. Are you just playing roles, or are your relationships real?

Can you conclude that your life has purpose and meaning? Have you

developed values and beliefs that go beyond your roles? What if you

could start over? What would you do differently? Can you trust that

there is some unity or harmony in life and that your life can fit in

somehow? These are important questions to resolve if one’s life is to

have meaning.

Meaning develops first from a deep, conscious,

accurate, and authentic understanding of oneself. Second, meaning then

arises from understanding oneself in relation to the world at large—that

is, the sense of how one’s life fits in relationship with the universe.

And third, meaning grows from authentic relations with others, which

allow expression for the first and a context for the second. It is

through our personal relations that we can express ourselves as the

unique individuals we are and how we can understand our practical

grounding within the universe.

Since, ultimately, you will be the one who has to give

your life meaning, what meaning do you give your life? Here are some

suggestions that might help you begin the process:

- If you were to write a “last lecture”—a speech that you would give if you knew you would die tomorrow—what would you say? Carnegie Mellon professor Randy Pausch (2008), dying at age 47, did just that.

- What have you learned thus far about the meaning of life that you could share with others?

- Recall and locate five works of art—stories, poems, music, paintings, and/or other forms of art that have had meaning for you. Share these with a friend or a family member. In what ways have they helped you find meaning?

- Describe what you see as your greatest accomplishment. Does it relate to the goals you set for yourself? To your purpose in life?

- Remember that great ideas and accomplishments, including yours, may not be valued or recognized until long after your life has ended.

- “What can you do now in your life so that one year or five years from now, you won’t look back and have…dismay about the new regrets you’ve accumulated? In other words, can you find a way to live without continuing to accumulate regrets?” (Yalom, 2008, p. 101).

A conclusion about existential issues and existential

depression is impossible because they are like a möbius strip that

continues seamlessly and endlessly. Yet we do need to help ourselves and

our bright youngsters cope with these difficult existential questions.

We cannot do anything about death; our existence is finite. However, we

can learn to accept those aspects of existence that we cannot change. We

can also feel understood and not so alone, and we can discover ways to

manage freedom and our sense of isolation so that they will give our

lives purpose. We can keep creating and developing ourselves, we can

keep working for positive and healthy relationships, and we can keep

trying to make a difference in the world, thereby creating meaning for

ourselves. Although we cannot eradicate the basic underlying bricks of

the existential wall, we can learn from Dabrowski that growth through

the discovery of authenticity within ourselves and the expression of our

authentic selves through authentic relationships may serve as a salve

to soothe these realities of our existence.

In coping with existential depression, we must realize

that existential concerns are not issues that can be dealt with only

once, but will probably need frequent revisiting and reconsideration. We

can support others and help them understand that disintegration is a

necessary step toward new growth and meaning—it can eventually be

positive. And finally, we can encourage these individuals to give

meaning to their own lives in whatever ways they can by adopting the

message of hope as expressed by the African-American poet Langston

Hughes in his poem Dreams.

Hold fast to dreams,

for if dreams die,

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.

Hold fast to dreams.

For if dreams go,

Life is a barren field

Covered with snow.

James T. Webb, Ph.D., ABPP-CL, has been recognized as

one of the 25 most influential psychologists nationally on gifted

education, and he consults with schools, pro grams and individuals about

social and emotional needs of gifted and talented children. In 1981,

Dr. Webb established SENG (Supporting Emotional Needs of Gifted

Children, Inc.), a national nonprofit organization that provides

information, training, conferences, and work shops, and he remains as

Chair of SENG’s Professional Advisory

Committee.

Dr. Webb was President of the Ohio Psychological

Association and a member of its Board of Trustees for seven years. He

has been in private practice as well as in various consulting positions

with clinics and hospitals. Dr. Webb was one of the founders of the

School of Professional Psychology at Wright State University, Dayton,

Ohio, where he was a Professor and Associate Dean. Earlier in his

career, Dr. Webb was a member of the graduate faculty in psychology at

Ohio University, and subsequently directed the Department of Psychology

at the Children’s Med i cal Center in Dayton, Ohio where he also was

Associate Clinical Professor in the Departments of Pediatrics and

Psychiatry at the Wright State University School of Medicine.

Dr. Webb is the lead author of five books and several DVDs about gifted children. Four of his books have won “Best Book” awards.

- Guiding the Gifted Child: A Practical Source for Parents and Teachers

- Grandparents’ Guide to Gifted Children

- Misdiagnosis and Dual Diagnoses of Gifted Children and Adults: ADHD, Bi polar, OCD, Asperger’s, Depression, and Other Disorders

- Gifted Parent Groups: The SENG Model, 2nd Edition

- A Parent’s Guide to Gifted Children

No comments:

Post a Comment